The purpose of this article is providing an Italian translation of a scene from one of the most influential Shakespearean works

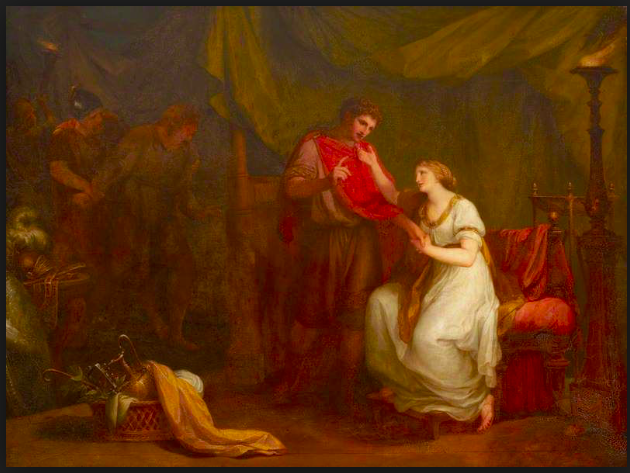

Dated back to 1602, Troilus and Cressida has as particularity two different plots. The first one, which also gives the title to the drama concerns the short but intense love story between Troilus, the Trojan prince and Cressida, Priamo’s, the Trojan king, daughter. Troilus pursues his interest towards the princess until he wins her heart. Their love is very short, though, since Cressida is shortly after sent to Greece, as a prisoner of war. As far as it concerns the second plot, it involves the majority of the play and is about the agreement that the Greek prince Nestor and the king of Ithaca Odysseus -or Ulysses, in some versions- make in order to push Achilles over his pride and persuade him to join the battlefield.

This drama isn’t a conventional tragedy, the main character Troilus, indeed, doesn’t die. This of course doesn’t make the ending of the play happier: it ends with a death, Ettore’s, the Trojan prince and the irreversible destruction of the bond between the two lovers. The storyline interchanges colloquial, light tones from an erotic play with those of the tragedy. There is a continual questioning on values like hierarchy, honour, and love itself. Its themes make the tragedy very deep, more modern than its own time.

Translation

From act II, scene 3.

Achille: Patroclo, non voglio parlare con nessuno. Vieni dentro con me Tersite. (esce)

Tersite: Quanti giochetti, che inganni, che furfanterie! E tutto per una puttana e un cornuto; una bella questione per stimolare le fazioni invidiose e sanguinarci su a morte. Che gli venga la serpigine, e la guerra e la lussuria li distruggano. (esce)

Agamennone: (a Patroclo) Dov’è Achille?

Patroclo: Nella sua tenda. Ma è indisposto, mio signore.

Agamennone: Che gli sia detto che noi siamo qui. Ha insultato i nostri messaggeri e noi rinviamo le nostre prerogative per venire a fargli visita. Gli sia detto così, qualora pensasse che non osiamo dar peso alla nostra posizione, o che non sappiamo chi noi siamo.

Patroclo: Vado a dirglielo.

Ulisse: Lo abbiamo visto all’ingresso della sua tenda. Non sta male.

Aiace: Sì, ha il male del leone. Ha il male della superbia nel cuore. E chiamatela melanconia, se proprio volete andargli incontro, ma mi ci gioco la testa: è superbia. Ma perché? Perché? Che almeno dica il motivo – una parola, mio signore. (Prende da parte Agamennone)

Nestore: Cosa muove Aiace ad abbaiargli contro in questo modo?

Ulisse: Achille gli ha preso il buffone.

Nestore: Ma chi? Tersite?

Ulisse: Lui.

Nestore: Se ha perso il suo interesse, ad Aiace mancherà anche la sostanza.

Ulisse: No. Vedete, il suo interesse è quello che gli ha portato via l’interesse: Achille.

Nestore: Meglio ancora! Desideriamo una discrepanza tra loro più che un’alleanza. Certo che l’unione era forte se è bastato uno sciocco a romperla.

Ulisse: Se la saggezza non lega l’amicizia, basta una sciocchezza impulsiva a scioglierla.

Comment

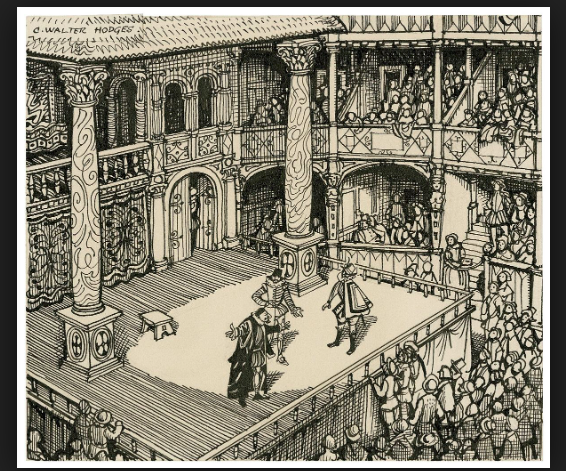

This scene from act II, scene 3 is a typical dialogue which is very suitable for theatre; even if the topic is historical, it is very easy to follow. There are no monologues, just a couple of longer lines. This makes the speech flows quickly, even in the longest lines, gives a good rhythm and helps the audience to follow the action. At this point of the play is noticeable how the whole attention is not focused on the actual important event, which is the Trojan war, but on the quarrels between characters, that should be considered a background action. This occurs because the idea of the characters that Shakespeare shows is not historical. According to Nadia Fusini’s introduction to the play, Shakespeare has the ability to disassemble values, destroy the ideology of the heroes, show the corruption and the depravation every characters has, regardless of the class they belong to. And this is exactly what he does in Troilus and Cressida.

Every character has an historical importance, and none of them is valued for what history taught about them. Considering only those appearing in this scene it’s very noticeable that Achilles acts like a child, Ajax is a puppet in Agamemnon’s hands, Ulysses and Nestor are the wise figures on one hand, while on the other they are the strategos of the game who try to arrange the situation for their own sake. Only Thersites, the fool, the apparently unimportant character, is the one who holds the key to the play. He understood for real how the situation come in succession and, unlike Pandarus, who is supposed to be wit and to act for the best but has personal justifications to his attitude, he’s the only one who sees and shows the play, the reality, for what it is.

Moving now to the analysis of the translation,

the thing that really matter to my translation is paying the adequate attention to how the vocabulary has changed over the centuries, in order to keep the most accurate meaning of the speech, to keep defined the role that every character has toward the other, also according to the context. Last but not least, I tried my best to recreate the word games in the most faithful way I could think of.

The Scene

The first character who speaks is Achilles; he is a superb demigod who has enough self esteem to decide whether to join the battle or remain inside his tent. The desire he expresses is not to talk to anybody. The will, if considering a late modern English approach, would have as translation “Non parlerò con nessuno”. What I considered is that the verb will expresses also a desire, in this case is not a modal, but has the meaning of “voglio” that can’t be implied. “Non voglio parlare con nessuno” is by far the best option. The line that follow is Thersites’. He has a longer line. Long lines interrupt the regular flood of the dialogue, but Thersites intervention is so important it can’t be split. In this line we have the resume, the core of the whole play which, as he says “il tutto per un cornuto e una puttana”. It seems like something not even worth all the problems it’s causing, still, it’s happening. This line was supposed to be a little bit longer in Italian, but I decided not to translate “all the argument is..” literally – tutta la questione gira intorno a..- because I considered the acting point of view , according to which this single line should be performed without breathing breaks; the literal translation might leave an actor out of breath, since the line after the semicolon has almost no spaces to take breaths, too.

Thersites is a character with much linguistic power; he is free to comment anything and insult anybody. He’s smart, acts like a fool, and can be cruel, if he wants. The idea of “sanguinarci su a morte” looks very real and accurate, and the cold, emotionless cruelty that Thersites has to express some ideas suggested to translate giving some cruelty to the form used. The end of his line introduces the issue of how words changed their meaning over the centuries.Confound has in this case a meaning which is not the same we use nowadays. As we know from David Cristal’s Think on my words, English, and, consequentially, Shakespeare language, have changed somehow. Keeping this in mind is fundamental when translating, otherwise the English that nowadays we know and speak would confuse the translator and terms might be translated with their modern meaning. Confound comes from Latin confundere that means “to confuse”, but the meaning Shakespeare uses of the word is given by the passage through Old French confondre that means “to destroy”. This explains also the use of lussuria. Lust is one of the deadly sin. A sin is something which might actually destroy somebody. It looked suitable next to confound.

Agamemnon is an important character.

He has an historical importance and consequentially he speaks with a higher register. He talks about appertainments, that according to shakespeareswords.com means prerogatives described on the online etymology dictionary as the “special rights or privilege granted to someone”. He also uses the word perchance which literally means “by chance”, which was an already existing word in Shakespeare language. The next line, that is Patroclus’ response to Agamemnon that he “shall say so” to Achilles. Shall comes from Proto-Germanic skal –that express the idea of an obligation, something that must really be done. That’s why his answer is “Vado a dirglielo”. For Ajax line we can feel the anger of the character towards Achilles. An anger expressed in a single sentence, which, once again is longer, but necessary to the action. Ajax says “If you will favor the man” that I decided to translate with “Se proprio volete andargli incontro” because gives me the idea of a deep disagree from Ajax to a justification that proposed himself.

He doesn’t want to help the man, at all. And the hand gesture on the scene would give the right intention to this line. In the case of Nestore’s line we find once again the use of will. In this case, the verb give the idea of the future, so I translated it as the modern auxiliary will, “will lack” as mancherà. Ulysses uses you toward Nestor because the use of you implied respect toward the person who the you refers to. When referring to someone belonging to a lower class, or less respected by the speaker, Shakespeare uses thou. In this case, you is translated with voi. There’s an opposition in the original English text given by the words fraction/faction in the sentence “Their fraction is more our wish than their faction” They’re opposite words and they also rhyme. I decided to keep the rhyme and use two Italian words as well opposite: discrepanza and alleanza.

Not only we have words with a Latin or Germanic origin, the language of Shakespeare is also made by a large number of neologism.

Composure said by Nestor in his last line is a neologism at Shakespeare’s time. It has its roots from composition developed in the late 14th century and it came from Latin compositionem, but this version of the world it’s first recorded in 1600. Another word coming from Latin appears in the last line of the translation. It’s the word amity. It’s from Old French amitie and earlier from Vulgar Latin amicitatem. I translated it with amicizia. To conclude, I tied together the words fool and folly in a word game which is actually common in Shakespeare’s plays. A consideration I need to make is that folly from Old French folie was something occurring from a foolish behavior. Sciocchezza could work in this term, but, according to the Online Etymology Dictionary, in Middle English the term included the meaning lewdness which is an obscene behaviour. I wanted to keep the word game sciocco/sciocchezza but it was clear that sciocchezza didn’t cover the whole meaning of folly; that’s why I added the word impulsiva. Acting impulsively might have any kind of consequence, even the most obscene.

articolo di

Martina Russo

Gli articoli di traduzione relativi a Troilus and Cressida provengono da riflessioni degli studenti della professoressa Plescia, la quale ha trattato il dramma e le varie proposte traduttive durante le sue lezioni.